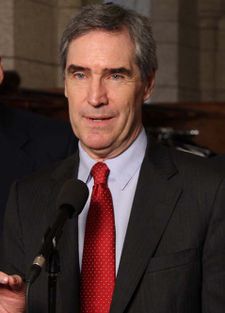

Michael Ignatieff

| The Honourable Michael Ignatieff PC MP |

|

|

|

|

Leader of the Opposition

|

|

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office December 10, 2008 |

|

| Monarch | Elizabeth II |

|---|---|

| Prime Minister | Stephen Harper |

| Preceded by | Stéphane Dion |

|

|

|

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office December 10, 2008 Acting until May 2, 2009 |

|

| Preceded by | Stéphane Dion |

|

Member of the Canadian Parliament

for Etobicoke-Lakeshore |

|

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office February 6, 2006 |

|

| Preceded by | Jean Augustine |

|

|

|

| Born | May 12, 1947 Toronto, Canada |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse(s) | Susan Barrowclough (1977–1997) Zsuzsanna Zsohar (1999–present) |

| Residence | Stornoway (Official) Toronto (Private) |

| Alma mater | University of Toronto University of Oxford Harvard University King's College, Cambridge |

| Profession | Author Screenwriter Journalist Professor Academic |

| Religion | Russian Orthodoxy |

| Signature | |

Michael Grant Ignatieff PC MP (pronounced /ɪɡˈnæti.əf/; born May 12, 1947) is the leader of the Liberal Party of Canada and Leader of the Official Opposition in Canada. Widely known for his work as a historian and author, Ignatieff held senior academic posts at the University of Cambridge, the University of Oxford, Harvard University and the University of Toronto before entering politics in 2006.

In the 2006 federal election, Ignatieff was elected to the House of Commons as the Member of Parliament for Etobicoke—Lakeshore. That same year, he ran for the leadership of the Liberal Party, ultimately conceding to Stéphane Dion after the fourth and final ballot. He served as the party's deputy leader under Dion, and held his seat in the 2008 federal election.

On November 14, 2008, Ignatieff announced his candidacy for the leadership of the Liberal Party[1] to succeed Dion. On December 10, he was formally declared the interim leader in a caucus meeting after all other candidates withdrew and backed his bid; his succession as leader was ratified at the party's May 2009 convention.[2]

Contents |

Family background

Ignatieff was born on May 12, 1947 in Toronto, the elder son of Russian-born Canadian diplomat George Ignatieff and his Canadian-born wife, Jessie Alison (née Grant). He numbers many prominent Canadian and Russian historical figures from both sides of his family among his ancestors.

His Canadian antecedents, whom Ignatieff describes as "high-minded Nova Scotians", were largely of Scots and English derivation and include his two maternal great-grandfathers, the Very Reverend Dr George Monro Grant, a 19th century Presbyterian minister who served as principal of Queen's University, and Sir George Parkin, a staunch imperialist, and leading proponent of the movement for the Federation of the British Empire.

More recently, his mother's younger brother was the Canadian Conservative political philosopher George Grant (1918–1988), author of Lament for a Nation, while his great-aunt was Alice Parkin Massey, the wife of Canada's first home-grown Governor General Vincent Massey.

His Russian forebears include the aristocratic families of Bibikov, Galitzine, Ignatyev, Karamzin, Maltsev, Meshchersky, Panin, and Tolstoy, and encompass many members of the old service nobility. His paternal grandfather, Count Paul Ignatieff, served as the last Tsarist Minister of Education (1915–1917), whose reputation as a liberal reformer led to his being spared from execution by the Bolsheviks. His patrilineal great-grandfather was Count Nikolay Pavlovich Ignatyev, the Russian Minister of the Interior under Tsar Alexander III, who is considered the architect of modern Bulgaria's independence from the Ottoman Empire. Via the latter's wife, Ignatieff descends from Field Marshal Kutuzov whose victory over Napoleon's Grande Armée at Smolensk in 1812 saved Russia from foreign subjugation.

In his book The Russian Album, Ignatieff acknowledges the importance of memory and discharges a felt obligation to his Russian forebears in the context of his paternal ancestors' own rich history. He makes no claims of ethnocentricity or Russian nationalism and explicitly distances himself from his ancestors' ability to constrain his own life by stating at the book's conclusion: "I do not believe in roots", explaining that his is a book written to keep faith with his paternal grandparents who died two years before his birth:

"I have not been on a voyage of self-discovery: I have just been keeping a promise to two people I never knew. These strangers are dear to me not because their lives contain the secret of my own, but because they saved their memory for my sake."

Until the April 2009 publication of his latest book, True Patriot Love, an exploration of four generations of his mother's paternal ancestors, the Grant family, Ignatieff had not made a similar investigation of his Canadian heritage, explaining this earlier dichotomy at the beginning of his 1987 work, The Russian Album:

"Between my two pasts, the Canadian and the Russian, I felt I had to choose. The exotic always exerts a stronger lure than the familiar and I was always my father's son. I chose the vanquished past, the past lost behind the revolution. I could count on my mother's inheritance: it was always there. It was my father's past that mattered to me, because it was one I had to recover, to make my own."

True Patriot Love seeks to answer his critics on this front, showcasing his maternal ancestors' deep involvement in the growth and advancement of Canada from colony to nationhood to well-known presence on the international scene.

Ignatieff's Maritime ancestors include New Brunswickers of Yorkshire, English, and New York, Dutch, origin who introduced both decidedly Tory and moderate Liberal strains of British imperialism and United Empire loyalism into Ignatieff's complex Canadian background.

These include Baptist turned Anglican, Upper Canada College principal, Sir George Parkin, from the Yorkshire English component, and his wife, Annie Connell Fisher whose British American-born Loyalist grandfather, of Dutch extraction, was Peter Fisher, the first historian of New Brunswick. One of her uncles, Charles Fisher, was a Father of Confederation, and later New Brunswick Liberal M.P., whose moderate loyalism had allowed him to head the first responsible government in colonial New Brunswick.

All these figures have lengthy biographies in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, and knowledge of them provides a counterbalance to Ignatieff's emphasis on his Presbyterian Grit, Liberal/Reform ancestry in True Patriot Love. They also add more clues to his own serial incarnations as an educator, historiographer, political philosopher, and politician, and show that what is a deep personal pedigree in these fields can only be partly explained by an exploration of the contribution of his Grant ancestors, or of his Russian forebears.

Ignatieff is fluent in both English and French, although he speaks French with a Metropolitan accent, and not with that of Quebec.

Early life

Ignatieff's family moved abroad regularly in his early childhood as his father rose in the diplomatic ranks. But at the age of 11, Ignatieff was sent back to Toronto to attend Upper Canada College as a boarder in 1959.[3] At UCC, Ignatieff was elected a school prefect as Head of Wedd's House, was the captain of the varsity soccer team, and served as editor-in-chief of the school's yearbook.[3] As well, Ignatieff volunteered for the Liberal Party during the 1965 federal election by canvassing the York South riding. He resumed his work for the Liberal Party in 1968, as a national youth organizer and party delegate for the Pierre Elliott Trudeau party leadership campaign.

University

After high school, Ignatieff studied history at the University of Toronto's Trinity College (B.A., 1969).[4] There, he met fellow student Bob Rae, from University College, who was a debating opponent and fourth-year roommate. After completing his undergraduate degree, Ignatieff took up his studies at the University of Oxford, where he studied under, and was influenced by, the famous liberal philosopher Sir Isaiah Berlin, about whom he would later write. While an undergraduate at the University of Toronto, he was a part-time reporter for The Globe and Mail in 1964–65.[5] In 1976, Ignatieff completed his Ph.D in History at Harvard University. He was granted a Cambridge M.A. by incorporation in 1978 on taking up a fellowship at King's College there.[4]

University professor, writer, broadcaster

He was an assistant professor of history at the University of British Columbia from 1976 to 1978. In 1978 he moved to the United Kingdom, where he held a senior research fellowship at King's College, Cambridge until 1984. He then left Cambridge for London, where he began to focus on his career as a writer and journalist. During this time, he travelled extensively. He also continued to lecture at universities in Europe and North America, and held teaching posts at Oxford, the University of London, the London School of Economics, the University of California and in France.

While living in the United Kingdom, Ignatieff became well-known as a broadcaster on radio and television. His best-known television work has been Voices on Channel 4, the BBC 2 discussion programme Thinking Aloud and BBC 2's arts programme, The Late Show. His documentary series Blood and Belonging: Journeys into the New Nationalism aired on BBC in 1993. He was also an editorial columnist for The Observer from 1990 to 1993. In 1998 he was on the first panel of the long-running BBC Radio discussion series In Our Time.

In 2000, Ignatieff accepted a position as the director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. In 2005, Ignatieff left Harvard to become the Chancellor Jackman Professor in Human Rights Policy at the University of Toronto and a senior fellow of the university's Munk Centre for International Studies.[6] He was then publicly mentioned as a possible Liberal candidate for the next federal election.

Family

Ignatieff is married to Hungarian-born Zsuzsanna M. Zsohar, and has two children, Theo and Sophie, from his first marriage to Londoner Susan Barrowclough.[7]

Ignatieff has a younger brother, Andrew, a community worker who assisted with Ignatieff's campaign.[3] Although he says he is not a "church guy", Ignatieff was raised Russian Orthodox and occasionally attends services with family.[8] He describes himself as neither an atheist nor a 'believer'. [2]

Recognition

Michael Ignatieff is a recognized historian, a fiction writer and public intellectual[9] who has written several books on international relations and nation building. His seventeen[10] fiction and non-fiction books have been translated into twelve languages. He has contributed articles to newspapers such as The Globe and Mail and The New York Times Magazine. Maclean's named him among the "Top 10 Canadian Who's Who" in 1997 and one of the "50 Most Influential Canadians Shaping Society" in 2002. In 2003, Maclean's named him Canada's "Sexiest Cerebral Man."[11]

Ignatieff's history of his family's experiences in nineteenth-century Russia (and subsequent exile), The Russian Album, won the Canadian 1987 Governor General's Award for Non-Fiction and the British Royal Society of Literature's Heinemann Prize. His 1998 biography of Isaiah Berlin was shortlisted for both the Jewish Quarterly Literary Prize for Non-Fiction and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize.

His text on Western interventionist policies and nation building, Virtual War: Kosovo and Beyond, analyzes the NATO bombing of Kosovo and its subsequent aftermath. It won the Orwell Prize for political non-fiction in 2001.[12] Ignatieff worked with the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty in preparing the report, The Responsibility to Protect, which examined the role of international involvement in Kosovo and Rwanda, and advocated a framework for 'humanitarian' intervention in future humanitarian crises. Ignatieff's general line is to highlight the moral imperative to intervene for humanitarian and other high motives, rejecting isolationism, but then drawing attention to practical and systematic limitations to successful interventions. His 2003 book, Empire Lite, argued that the post-intervention efforts in Kosovo, Iraq, and Afghanistan were under-equipped to deal with the near-intractable problems they were facing.

His book on the dangers of ethnic nationalism in the post-Cold War period, Blood and Belonging: Journeys into the New Nationalism, won the Gordon Montador Award for Best Canadian Book on Social Issues and the University of Toronto's Lionel Gelber Prize.[13] Blood and Belonging was based on Ignatieff's Gemini Award winning 1993 television series of the same name.

In 2004, he published The Lesser Evil: Political Ethics in an Age of Terror, a philosophical work analyzing human rights in the post-9/11 world. The book was a finalist for the Lionel Gelber Prize, and attracted considerable attention for its attempts to reconcile the democratic ideals of western liberal societies with the often-coercive nature of the War on Terrorism.

Ignatieff also writes fiction; one of his novels, Scar Tissue, was short-listed for the Booker Prize. In addition to writing, he has been a guest lecturer in a variety of settings. He delivered the Massey Lectures in 2000. Entitled The Rights Revolution, the series was released in print later that year. He has been a participant and panel leader at the World Economic Forum in Geneva.

Ignatieff was ranked 37th on a list of top public intellectuals prepared by Prospect and Foreign Policy magazines in 2005.[9]

Writings

Ignatieff has been described by the British Arts Council as "an extraordinarily versatile writer," in both the style and the subjects he writes about.[14] His fictional works, Asya, Scar Tissue, and Charlie Johnson in the Flames cover, respectively, the life and travels of a Russian girl, the disintegration of one's mother due to neurological disease, and the haunting memories of a journalist in Kosovo. In all three works, however, one sees elements of the author's own life coming through. For instance, Ignatieff travelled to the Balkans and Kurdistan while working as a journalist, witnessing first hand the consequences of modern ethnic warfare. Similarly, his historical memoir, The Russian Album, traces his family's life in Russia and their troubles and subsequent emigration as a result of the Bolshevik Revolution.

A historian by training, he wrote A Just Measure of Pain, a history of prisons during the Industrial Revolution. His biography of Isaiah Berlin reveals the strong impression the celebrated philosopher made on Ignatieff. Philosophical writings by Ignatieff include The Needs of Strangers and The Rights Revolution. The latter work explores social welfare and community, and shows Berlin's influence on Ignatieff. These tie closely to Ignatieff's political writings on national self-determination and the imperatives of democratic self-government. Ignatieff has also written extensively on international affairs.[14]

Blood and Belonging, a 1993 work, explores the duality of nationalism, from Yugoslavia to Northern Ireland. It is the first of a trilogy of books that explore modern conflicts. The Warrior's Honour, published in 1998, deals with ethnically motivated conflicts, including the conflicts in Afghanistan and Rwanda. The final book, Virtual War, describes the problems of modern peacekeeping, with special reference to the NATO presence in Kosovo.

Canadian culture and human rights

In The Rights Revolution, Ignatieff identifies three aspects of Canada's approach to human rights that give the country its distinctive culture: 1) On moral issues, Canadian law is secular and liberal, approximating European standards more closely than American ones; 2) Canadian political culture is socially democratic, and Canadians take it for granted that citizens have the right to free health care and public assistance; 3) Canadians place a particular emphasis on group rights, expressed in Quebec's language laws and in treaty agreements that recognize collective aboriginal rights. "Apart from New Zealand, no other country has given such recognition to the idea of group rights," he writes.[15]

Ignatieff states that despite its admirable commitment to equality and group rights, Canadian society still places an unjust burden on women and gays and lesbians, and he says it is still difficult for newcomers of non-British or French descent to form an enduring sense of citizenship. Ignatieff attributes this to the "patch-work quilt of distinctive societies," emphasizing that civic bonds will only be easier when the understanding of Canada as a multinational community is more widely shared.

International affairs

Ignatieff has written extensively on international development, peacekeeping and the international responsibilities of Western nations. Critical of the limited-risk approach practiced by NATO in conflicts like the Kosovo War and the Rwandan Genocide, he says that there should be more active involvement and larger scale deployment of land forces by Western nations in future conflicts in the developing world. Ignatieff attempts to distinguish his approach from Neo-conservativism because the motives of the foreign engagement he advocates are essentially altruistic rather than selfserving.[16]

In this vein, Ignatieff was originally a prominent supporter of the 2003 Invasion of Iraq.[17] Ignatieff said that the United States established "an empire lite, a global hegemony whose grace notes are free markets, human rights and democracy, enforced by the most awesome military power the world has ever known." The burden of that empire, he says, obliged the United States to expend itself unseating Iraqi president Saddam Hussein in the interests of international security and human rights. Ignatieff initially accepted the position of the George W. Bush administration: that containment through sanctions and threats would not prevent Hussein from selling weapons of mass destruction to international terrorists. Ignatieff believed that those weapons were still being developed in Iraq.[18] Moreover, according to Ignatieff, "what Saddam Hussein had done to the Kurds and the Shia" in Iraq was sufficient justification for the invasion.[19][20]

In the years following the invasion, Ignatieff reiterated his support for the war, if not the method in which it was conducted. "I supported an administration whose intentions I didn't trust," he averred, "believing that the consequences would repay the gamble. Now I realize that intentions do shape consequences."[17] He eventually recanted his support for the war entirely. In a 2007 New York Times Magazine article, he wrote: "The unfolding catastrophe in Iraq has condemned the political judgment of a president, but it has also condemned the judgment of many others, myself included, who as commentators supported the invasion." Ignatieff partly interpreted what he now saw as his particular errors of judgment, by presenting them as typical of academics and intellectuals in general, whom he characterised as "generalizing and interpreting particular facts as instances of some big idea". In politics, by contrast, "Specifics matter more than generalities".[21]

On June 3, 2008, Michael Ignatieff voted in support of a motion in the House of Commons calling on the government to "allow conscientious objectors...to a war not sanctioned by the United Nations...to...remain in Canada..."[22][23][24]

Ignatieff has also spoken on the issue of Canadian participation in the North American Missile Defence Shield. In "Virtual War," Ignatieff refers to the likelihood of America developing a MDS to protect the United States. Nowhere did Ignatieff voice support for Canadian participation in such a scheme.[25] Further, in October 2006, Ignatieff indicated that he personally would not support ballistic missile defence nor the weaponization of space.[26]

In 2005 Ignatieff delivered the Amnesty 2005 Lecture at Trinity College in Dublin where-in he provided evidence to support his theory that; "We wouldn't have international human rights without the leadership of the United States".[27]

The Lesser Evil approach

Ignatieff has argued that Western democracies may have to resort to "lesser evils" like indefinite detention of suspects, coercive interrogations,[28] assassinations, and pre-emptive wars in order to combat the greater evil of terrorism.[29] He states that as a result, societies should strengthen their democratic institutions to keep these necessary evils from becoming as offensive to freedom and democracy as the threats they are meant to prevent.[30] The 'Lesser Evil' approach has been criticized by some prominent human rights advocates, like Conor Gearty, for incorporating a problematic form of moral language that can be used to legitimize forms of torture.[31] But other human rights advocates, like Human Rights Watch's Kenneth Roth, have defended Ignatieff, saying his work attempts a difficult balance between competing values.[32] In the context of this "lesser evil" analysis, Ignatieff has discussed whether or not liberal democracies should employ coercive interrogation and torture. Ignatieff has adamantly maintained that he supports a complete ban on torture.[33] His definition of torture, according to his 2004 Op-ed in the New York Times, does not include "forms of sleep deprivation that do not result in lasting harm to mental or physical health, together with disinformation and disorientation (like keeping prisoners in hoods)."[34]

Political career

In 2004, three Liberal organizers, former Liberal candidate Alfred Apps, Ian Davey (son of Senator Keith Davey) and lawyer Daniel Brock, travelled to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to convince Ignatieff to move back to Canada and run for the Canadian House of Commons, and to consider a possible bid for the Liberal leadership should Paul Martin retire.[35] Liberal Party stalwart, Rocco Rossi had previously mentioned to Davey that Davey's father had said that Ignatieff had the makings of a prime minister.[36] As a result of the activities of Apps,Brock and Davey, in January 2005, speculation began in the press that Ignatieff could be a star candidate for the Liberals in the next election, and possibly a candidate to succeed Paul Martin, then the leader of the governing Liberal Party of Canada.

After months of rumours and repeated denials, Ignatieff confirmed in November 2005 that he intended to run for a seat in the House of Commons in the winter 2006 election. It was announced that Ignatieff would seek the Liberal nomination in the Toronto riding of Etobicoke—Lakeshore.

Some Ukrainian-Canadian members of the riding association objected to the nomination, citing a perceived anti-Ukrainian sentiment in Blood and Belonging, where Ignatieff discusses Russian stereotypes of Ukrainians.[37] Critics also questioned his commitment to Canada, pointing out that Ignatieff had lived outside of Canada for more than 30 years and had referred to himself as an American many times. When asked about it by Peter Newman in a Maclean's interview published on April 6, 2006, Ignatieff said: "Sometimes you want to increase your influence over your audience by appropriating their voice, but it was a mistake. Every single one of the students from 85 countries who took my courses at Harvard knew one thing about me: I was that funny Canadian."[38] Two other candidates filed for the nomination but were disqualified (one, because he was not a member of the party and the second because he had failed to resign from his position on the riding association executive). Ignatieff went on to defeat the Conservative candidate by a margin of roughly 5,000 votes to win the seat.[39]

Leadership bid

After the Liberal government was defeated in the January 2006 federal election, Paul Martin resigned from party leadership. On April 7, 2006, Ignatieff announced his candidacy in the upcoming Liberal leadership race, joining several others who had already declared their candidacy.

Ignatieff received several high profile endorsements of his candidacy. His campaign was headed by Senator David Smith, who had been a Chrétien organizer, along with Ian Davey, Daniel Brock, Alfred Apps and Paul Lalonde, a Toronto lawyer and son of Marc Lalonde.[40]

An impressive team of policy advisors was assembled, led by Toronto lawyer Brad Davis, and including Brock, fellow lawyers Mark Sakamoto, Sachin Aggarwal, Jason Rosychuck, Jon Penney, Nigel Marshman, Alex Mazer, Will Amos, and Alix Dostal, former Ignatieff student Jeff Anders, banker Clint Davis, economists Blair Stransky, Leslie Church and Ellis Westwood, and Liberal operatives Alexis Levine, Marc Gendron, Mike Pal, Julie Dzerowicz, Patrice Ryan, Taylor Owen and Jamie Macdonald.[41]

Following the selection of delegates in the party's "Super Weekend" exercise on the last weekend of September, Ignatieff gained more support from delegates than other candidates with 30% voting for him.

In August 2006, Ignatieff said he was "not losing any sleep" over dozens of civilian deaths caused by Israel's attack on Qana during its military actions in Lebanon.[42] Ignatieff recanted those words the following week. Then, on October 11, 2006, Ignatieff described the Qana attack as a war crime (committed by Israel). Susan Kadis, who had previously been Ignatieff's campaign co-chair, withdrew her support following the comment. Other Liberal leadership candidates have also criticized Ignatieff's comments.[43] Ariela Cotler, a Jewish community leader and the wife of prominent Liberal MP Irwin Cotler, left the party following Ignatieff's comments.[44] Ignatieff later qualified his statement, saying "Whether war crimes were committed in the attack on Qana is for international bodies to determine. That doesn't change the fact that Qana was a terrible tragedy."[45]

On October 14, Ignatieff announced that he would visit Israel, to meet with Israeli and Palestinian leaders and "learn first-hand their view of the situation". He noted that Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and Israel's own B'Tselem have stated that war crimes were committed in Qana, describing the suggestion as "a serious matter precisely because Israel has a record of compliance, concern and respect for the laws of war and human rights"[46] Ignatieff added that he would not meet with Palestinian leaders who did not recognize Israel. However, the Jewish organization sponsoring the trip subsequently cancelled it, because of too much media attention.

Montreal Convention

At the leadership convention in Montreal, taking place at Palais des Congrès, Ignatieff entered as the apparent front-runner, having elected more delegates to the convention than any other contender. However, polls consistently showed he had weak second-ballot support, and those delegates not already tied to him would be unlikely to support him later.

On December 1, 2006, Michael Ignatieff led the leadership candidates on the first ballot, garnering 29% support. The subsequent ballots were cast the following day, and Ignatieff managed a small increase, to 31% on the second ballot, good enough to maintain his lead over Bob Rae, who had attracted 24% support, and Stéphane Dion, who garnered 20%. However, due to massive movement towards Stéphane Dion by delegates who supported Gerard Kennedy, Ignatieff dropped to second on the third ballot. Shortly before voting for the third ballot was completed, with the realization that there was a Dion-Kennedy pact, Ignatieff campaign co-chair Denis Coderre made an appeal to Rae to join forces and prevent the ardent federalist Dion from winning the leadership (on the basis that Dion's federalism would alienate Quebecers), but Rae turned down the offer and opted to release his delegates.[47] With the help of the Kennedy delegates, Dion jumped up to 37% support on the third ballot, in contrast to Ignatieff's 34% and Rae's 29%. Bob Rae was eliminated and the bulk of his delegates opted to vote for Dion rather than Ignatieff. In the fourth and final round of voting, Ignatieff took 2084 votes and lost the contest to Stéphane Dion, who won with 2521 votes.[48]

Lauren P. S. Epstein, the former prime minister of the Harvard Canadian Club, commented on the loss: "What it came down to in the final vote was that the liberal delegates were looking for someone who was more likely to unite the party; Ignatieff had ardent supporters, but at the same time, he had people who would never under any circumstances support him."[49]

Ignatieff confirmed that he would run as the Liberal MP for Etobicoke—Lakeshore in the next federal election.[50]

Deputy leadership

On December 18, 2006, new Liberal leader Stéphane Dion named Ignatieff his deputy leader, in line with Dion's plan to give high-ranking positions to each of his former leadership rivals.[51]

During three by-elections held on September 18, 2007, the Halifax Chronicle-Herald reported that unidentified Dion supporters were accusing Ignatieff's supporters of undermining by-election efforts, with the goal of showing that Dion could not hold on to the party's Quebec base.[52] Susan Delacourt of the Toronto Star described this as a recurring issue in the party with the leadership runner-up.[53][53] The National Post referred to the affair as, "Discreet signs of a mutiny."[54] Although Ignatieff called Dion to deny the allegations, the Globe and Mail cited the NDP's widening lead after the article's release, suggested that the report had a negative impact on the Liberals' morale.[55] The Liberals were defeated in their former stronghold of Outremont.

Since then, Ignatieff has urged the Liberals to put aside their differences, saying "united we win, divided we lose".[56]

Interim leadership of the Liberal Party

Dion announced that he would schedule his departure as Liberal leader for the next party convention, after the Liberals lost seats and support in the 40th general election. Ignatieff held a news conference on November 13, 2008, to once again announce his candidacy for the leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada.[57]

When the Liberals reached an accord with the other opposition parties to form a coalition and defeat the government, Ignatieff reluctantly endorsed it. He was reportedly uncomfortable with a coalition with the NDP and outside support from the Bloc Québécois, and has been described as one of the last Liberals to sign on.[58][59][60] After the announcement to prorogue Parliament, delaying the non-confidence motion until January 2009, Dion announced his intention to stay on as interim leader until the party selected a new one.[60]

Leadership contender Dominic LeBlanc dropped out and threw his support behind Ignatieff. On December 9, the other remaining opponent for the Liberal Party leadership, Bob Rae, withdrew from the race, leaving Ignatieff as the presumptive winner.[61] On December 10, he was formally declared the interim leader in a caucus meeting, and his position was ratified at the May 2009 convention.[2] On February 19, 2009, during his visit to Canada, American President Barack Obama met with Ignatieff to discuss topics ranging from climate change to Afghanistan.

Leadership

On May 2, 2009, Ignatieff was officially endorsed as the leader of the Liberal Party by 97% of delegates at the party convention in Vancouver.[62] The vote was mostly a formality as there were no other candidates for the leadership.

On August 31, 2009, Ignatieff announced that the Liberal Party would withdraw support for the government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper. However, the NDP under Jack Layton abstained and the Conservatives survived the confidence motion.[63] Ignatieff's attempt to force a September 2009 election was reported as a miscalculation, as polls showed that most Canadians did not want another election. Ignatieff's popularity as well as that of the Liberals dropped off considerably immediately afterwards.[64]

Notable political stances

Extension of Canada's Afghanistan mission

Since his election to Parliament, Ignatieff has been one of the few[65] opposition members supporting the minority Conservative government's commitment to Canadian military activity in Afghanistan. Prime Minister Stephen Harper called a vote in the House of Commons for May 17, 2006, on extending the Canadian Forces current deployment in Afghanistan until February 2009. During the debate, Ignatieff expressed his "unequivocal support for the troops in Afghanistan, for the mission, and also for the renewal of the mission." He argued that the Afghanistan mission tests the success of Canada's shift from "the peacekeeping paradigm to the peace-enforcement paradigm," the latter combining "military, reconstruction and humanitarian efforts together."[66][67]

The opposition Liberal caucus of 102 MPs was divided, with 24 MPs supporting the extension, 66 voting against, and 12 abstentions. Among Liberal leadership candidates, Ignatieff and Scott Brison voted for the extension. Ignatieff led the largest Liberal contingent of votes in favour, with at least five of his caucus supporters voting along with him to extend the mission.[68] The vote was 149–145 for extending the military deployment.[67] Following the vote, Harper shook Ignatieff's hand.[69]

In a subsequent campaign appearance, Ignatieff reiterated his view of the mission in Afghanistan. He stated: "the thing that Canadians have to understand about Afghanistan is that we are well past the era of Pearsonian peacekeeping."[70]

Quebec as a nation

On October 21, 2006, the Quebec wing of the Liberal Party of Canada adopted a resolution that called for the entire Liberal Party of Canada to recognize "the Quebec nation", and to form a task force to find possible ways to "officialize this historical and social reality."[71] Ignatieff endorsed the resolution and suggested that it may need to be entrenched into the Constitution of Canada at some point down the road. Two of his former leadership rivals, Bob Rae and Stéphane Dion have agreed on the nation label, but do not want to reopen the Constitution.[72] Recognizing Quebec's "distinct" nature in the Constitution was attempted previously by Prime Minister Brian Mulroney with the Meech Lake Accord and the Charlottetown Accord, as well as by a motion by then-Prime Minister Jean Chrétien in 1995.

On November 22, 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper declared his support for the Québécois being recognized as a nation within Canada. This recognition of the "Québécois nation" is essentially of symbolic political nature, and represents no constitutional changes or legal consequences. Prime Minister Harper introduced a motion to the House of Commons that called for the recognition "that the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada". The motion was carried by the House of Commons on November 27, 2006, by a vote of 266–16, with every party supporting the motion, and a handful of Liberal members voting against, as well as independent MP Garth Turner. Following the adoption of this motion, the Liberal motion was withdrawn, and not presented to the convention.

Climate change policy

During the Liberal leadership race in 2006, Ignatieff advocated strong measures, including measures to address climate change.[73]

Following the 2008 election, he shifted his approach. In a speech to the Edmonton Chamber of Commerce in February, 2009, he said: "You've got to work with the grain of Canadians and not against them. I think we learned a lesson in the last election."[74]

Honorary degrees

Michael Ignatieff as of June 2009 has received 11 Honorary Doctorates.

Bishop's University in Lennoxville, Quebec in 1995

Bishop's University in Lennoxville, Quebec in 1995 University of Stirling in Stirling, Scotland (D.Univ) on June 28, 1996[75]

University of Stirling in Stirling, Scotland (D.Univ) on June 28, 1996[75] Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario (LL.D) on October 25, 2001[76]

Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario (LL.D) on October 25, 2001[76] University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario (D.Litt) on October 26, 2001[77]

University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario (D.Litt) on October 26, 2001[77] University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, New Brunswick (D.Litt) in 2001[78]

University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, New Brunswick (D.Litt) in 2001[78] McGill University in Montreal, Quebec (D.Litt) on June 17, 2002[79]

McGill University in Montreal, Quebec (D.Litt) on June 17, 2002[79] University of Regina in Regina, Saskatchewan (LL.D) on May 28, 2003[80]

University of Regina in Regina, Saskatchewan (LL.D) on May 28, 2003[80] Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington (LL.D) in 2004[81]

Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington (LL.D) in 2004[81] Niagara University in Lewiston, New York, USA (DHL) May 21, 2006[82]

Niagara University in Lewiston, New York, USA (DHL) May 21, 2006[82]

Bibliography

Screenplays

- Onegin, 1999 (with Peter Ettedgui)

- 1919, 1985 (with Hugh Brody)

Drama

- Dialogue in the Dark, for the BBC

Fiction

- Asya, 1991

- Scar Tissue, 1993

- Charlie Johnson in the Flames, 2005

Non-fiction

- A Just Measure of Pain: Penitentiaries in the Industrial Revolution, 1780–1850, 1978

- (ed. with István Hont) Wealth and Virtue: The Shaping of Political Economy in the Scottish Enlightenment, Cambridge University Press , 1983. ISBN 0-521-23397-6

- The Needs of Strangers, 1984

- The Russian Album, 1987

- Blood and Belonging: Journeys Into the New Nationalism, 1994

- Warrior's Honour: Ethnic War and the Modern Conscience, 1997

- Isaiah Berlin: A Life, 1998

- Virtual War: Kosovo and Beyond, 2000

- The Rights Revolution, Viking, 2000

- Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry, Anansi Press Ltd, 2001

- Empire Lite: Nation-Building in Bosnia, Kosovo and Afghanistan, Minerva, 2003

- The Lesser Evil: Political Ethics in an Age of Terror, Princeton University Press, 2004 (2003 Gifford Lectures; sample chapters)

- American Exceptionalism and Human Rights (ed.), Princeton University Press, 2005.

- True Patriot Love, Penguin Group Canada, 2009.

Recent articles

- Getting Iraq Wrong, The New York Times Magazine, August 5, 2007.

- What I Would Do If I Were The Prime Minister. Maclean's, September 4, 2006.

- The Broken Contract, The New York Times Magazine, September 25, 2005.

- Iranian Lessons, The New York Times Magazine, July 17, 2005.

- Who Are Americans to Think That Freedom Is Theirs to Spread?, The New York Times Magazine, June 26, 2005.

- The Uncommitted, The New York Times Magazine, January 30, 2005.

- The Terrorist as Auteur, The New York Times Magazine, November 14, 2004.

- Mirage in the Desert, The New York Times Magazine, June 27, 2004.

- Could We Lose the War on Terror?: Lesser Evils, (cover story), The New York Times Magazine, May 2, 2004.

- The Year of Living Dangerously, The New York Times Magazine, March 14, 2004.

- Arms and the Inspector, Los Angeles Times, March 14, 2004.

- Peace, Order and Good Government: A Foreign Policy Agenda for Canada, OD Skelton Lecture, Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Ottawa, March 12, 2004.

- Why America Must Know Its Limits, Financial Times, December 24, 2003.

- A Mess of Intervention. Peacekeeping. Pre-emption. Liberation. Revenge. When should we send in the Troops?, The New York Times Magazine [cover story], September 7, 2003.

- I am Iraq, The New York Times Magazine, March 31, 2003 [Reprinted in The Guardian and The National Post].

- American Empire: The Burden, (cover story), The New York Times Magazine, January 5, 2003.

- Acceptance Speech from the 2003 Hannah Arendt Prize for Political Thinking

- Mission Impossible?, A Review of A Bed for the Night: Humanitarianism in Crisis, by David Rieff (Simon and Schuster, 2002), Printed in The New York Review of Books, December 19, 2002.

- When a Bridge Is Not a Bridge, New York Times Magazine, October 27, 2002.

- The Divided West, The Financial Times, August 31, 2002.

- Nation Building Lite, (cover story) The New York Times Magazine, July 28, 2002.

- The Rights Stuff, New York Times of Books, June 13, 2002.

- No Exceptions?, Legal Affairs, May/June 2002.

- Why Bush Must Send in His Troops, The Guardian, April 19, 2002.

- Barbarians at the Gates?, The New York Times Book Review, February 18, 2002.

- Is the Human Rights Era Ending?, New York Times, February 5, 2002.

- Intervention and State Failure, Dissent, Winter 2002.

- Kaboul-Sarajevo: Les nouvelles frontières de l'empire, Seuil, 2002.

See also

- List of Canadian Leaders of the Opposition

- List of Canadian Leaders of the Opposition in the Senate

- Official Opposition (Canada)

References

- ↑ Whittington, Les (November 14, 2008). "Ignatieff vows a new course". Toronto: thestar.com. http://www.thestar.com/article/536753. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Ignatieff named interim Liberal leader". CBC News. 2008-12-10. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2008/12/10/ignatieff-caucus.html. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Valpy, Michael (August 26, 2006). "Being Michael Ignatieff". Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/RTGAM.20060825.wxboat26/BNStory/National/home/?pageRequested=all. Retrieved 2006-09-04.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Canadian Who's Who, 2005, p. 629, col. 1

- ↑ "January 24, 2001". Bulletin.uwaterloo.ca. 2001-01-24. http://www.bulletin.uwaterloo.ca/2001/jan/24we.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Michael Ignatieff". Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. http://www.cceia.org/people/data/michael_ignatieff.html.

- ↑ Owen, Arthur. "Descendants of Charles Oulton and Abigail Fillmore". http://arthur.owen.tripod.com/Oulton/b16362.htm. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ Michael Valpy on Michael Ignatieff. Interview with Michael Valpy. Globe and Mail. August 28, 2006.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "The Prospect/FP Top 100 Public Intellectuals.". http://www.infoplease.com/spot/topintellectuals.html. Retrieved 2006-08-28.

- ↑ "Michael Ignatieff has 'big' vision for Canada – CTV News". Ctv.ca. 2009-04-17. http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20090417/ignatieff_090417?s_name=&no_ads=. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Liberal.ca Biography of Michael Ignatieff". http://www.liberal.ca/bio_e.aspx?&id=35023. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ http://www.theorwellprize.co.uk/the-award/winners-books.aspx?year=277

- ↑ "The Lionel Gelber Prize". http://www.utoronto.ca/mcis/gelber/. Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Michael Ignatieff at Contemporary Writers". http://www.contemporarywriters.com/authors/?p=auth141. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ↑ Ignatieff, Michael (2000). The Rights Revolution. House of Anansi Press. ISBN 0-88784-656-4.

- ↑ Empire Lite: Nation-Building in Bosnia, Kosovo and Afghanistan, Minerva, 2003

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Ignatieff, Michael (March 14, 2004). "The Year of Living Dangerously". The New York Times Magazine. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/14/magazine/14WWLN.html?ex=1155441600&en=702afeea45f58a4f&ei=5070. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ Ignatieff, Michael (January 5, 2003). "The Burden". The New York Times Magazine. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B03E6DA143FF936A35752C0A9659C8B63&scp=1&sq=The%20Burden%20Ignatieff&st=cse. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ Ignatieff, Michael (March 30, 2006). "Canada and the World". The Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/RTGAM.20060330.wignatiefftext0330/BNStory/Front/?&pageRequested=all&print=true. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ Finlay, Mary Lou; Budd, Barbara (April 7, 2006). "As it Happens". CBC Radio. http://www.cbc.ca/radioshows/AS_IT_HAPPENS/20060407.shtml. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ Michael, Ignatieff (April 5, 2007). "Getting Iraq Wrong". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/05/magazine/05iraq-t.html?_r=1&ex=1343966400&en=13354304. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ↑ Smith, Joanna (2008-06-03). "MPs vote to give asylum to U.S. military deserters". The Toronto Star. http://www.thestar.com/News/Canada/article/436575. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- ↑ "Report – Iraq War Resisters / Rapport –Opposants à la guerre en Irak". House of Commons / Chambre des Communes, Ottawa, Canada. http://cmte.parl.gc.ca/cmte/CommitteePublication.aspx?SourceId=222011. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ↑ "Official Report * Table of Contents * Number 104 (Official Version)". House of Commons / Chambre des Communes, Ottawa, Canada. http://www2.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?Language=E&Mode=1&Parl=39&Ses=2&DocId=3543213#Int-2506938. Retrieved 2008-06-09.

- ↑ Paul, Derek (October–December 2000). "Review: Virtual War". Peace Magazine. http://www.peacemagazine.org/archive/v16n4p26.htm. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ O'Neill, Juliet (October 17, 2006). "Ignatieff against Canadian role in U.S. missile defence plan". Ottawa Citizen. http://www.canada.com/topics/news/politics/story.html?id=f56c529c-c7c8-4133-8f9f-69be8ed7f3d0&k=65028.

- ↑ "Program Information – IMC Ã: Amnesty Lecture 2005: Michael Ignatieff at Trinity College Dublin, Ireland|A-Infos Radio Project". Radio4all.net. 2005-01-13. http://www.radio4all.net/index.php/program/10935. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ McQuaig, Linda (2007). "Sidekicks to American Empire". Random House. http://thetyee.ca/Books/2007/05/01/McQuaig.

- ↑ "Worldbeaters: Michael Ignatieff". New Internationalist Magazine. 2005. http://www.newint.org/issue385/worldbeaters.htm.

- ↑ Ignatieff, Michael (May 2, 2004). "Lesser Evils (Op-Ed)". New York Times Magazine. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9507E6DA1F3AF931A35756C0A9629C8B63&scp=1&sq=lesser%20evils%20Ignatieff&st=cse. Retrieved 2006-09-24.

- ↑ Gearty, Conor (January 2005). "Legitimising torture – with a little help". Index on Censorship: Torture – A User's Manual. http://www.indexonline.org/en/news/articles/2005/1/international-legitimising-torture-with-a-li.shtml.

- ↑ Usborne, David (January 21, 2006). "Michael Ignatieff: Under siege". London: The Independent. http://news.independent.co.uk/people/profiles/article340032.ece.

- ↑ Ignatieff, Michael (April 2006). "If torture works...". Prospect. http://www.prospect-magazine.co.uk/article_details.php?id=7374.

- ↑ Ignatieff, Michael (May 2, 2004). "Lesser Evils (Op-Ed)". New York Times Magazine. http://www.hks.harvard.edu/cchrp/pdf/MI.Lesser%20Evils.5.2.pdf. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ Global TV News (2008)."Election2008 Key Candidates Michael Ignatieff." Global.Retrieved on: March 17,2010

- ↑ Geddes, John (September 4, 2006). "Rainmaker's" Son Backs Ignatieff." Maclean's. Retrieved on: April 14, 2008.

- ↑ CTV.ca News Staff (November 27, 2005). "Toronto group opposes Ignatieff's election bid". http://toronto.ctv.ca/servlet/an/local/CTVNews/20051127/ignatieff_election_051127/20051127/?hub=TorontoHome. Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ↑ Newman, Peter C. (April 6, 2006). "Q&A with Liberal leadership contender Michael Ignatieff". Maclean's. http://www.macleans.ca/topstories/politics/article.jsp?content=20060410_124769_124769. Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ↑ http://www.elections.ca/scripts/OVR2006/default.html

- ↑ Geddes, John (March 29, 2006). "Bill Graham's big job". Maclean's. http://www.macleans.ca/topstories/politics/article.jsp?content=20060403_124360_124360. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ "A Liberal Revolution". National Post. September 26, 2006. http://www.politiquebec.com/forum/viewtopic.php?t=20984&sid=d9beef2e4b316dd9e935103900d8e2ec. Retrieved 2006-10-11.

- ↑ "Ignatieff admits gaffe over Mideast conflict". CTV. 10 Augusr 2006.

- ↑ Bryden, Joan (October 12, 2006). "Campaign organizer abandons Ignatieff over war crimes comment". Montreal Gazette. http://www.canada.com/montrealgazette/story.html?id=80789bca-0e55-4e09-a027-9766b4deb520&k=3758.

- ↑ "Cotler's wife quits Liberals over Ignatieff comments". Canadian Press. October 13, 2006.

- ↑ Chris Wattie and Allan Woods, "Ignatieff fights back over Mideast", Calgary Herald, October 14, 2006, A13.

- ↑ Louise Brown, "Ignatieff set to visit Israel", Toronto Star, October 14, 2006, A20.

- ↑ "'Gesture' might have helped trigger Dion win". Canadian Press. December 2, 2006. http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20061202/liberal_balloting_061202/20061202?hub=TopStories.

- ↑ Campbell, Clark (December 2, 2006). "Dion surges to victory, defeating Ignatieff". The Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/RTGAM.20061202.wlibsfinalballot1202/BNStory/LiberalBackgrounder/home.

- ↑ "Ignatieff Loses Bid for Party Leadership.". http://www.thecrimson.com/article.aspx?ref=516158.

- ↑ "Ignatieff, Rae indicate they'll run in next election". CBC News. December 4, 2006. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2006/12/03/iggy-rae.html. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ↑ "Ignatieff tapped as Liberal deputy leader". CBC News Online. December 18, 2006. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2006/12/18/ignatieff.html.

- ↑ Susan Delacourt (September 18, 2007). "Liberal grumbling began even before crushing loss." the star.com. Retrieved on: October 6, 2007.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Susan Delacourt (September 22, 2007). "The Liberal affliction: Runner-up syndrome." the star.com. Retrieved on: October 6, 2007.

- ↑ Craig Offman (September 22, 2007). "Discreet signs of a mutiny.' The National Post. Retrieved on: October 6, 2007.

- ↑ Ignatieff called to reassure Dion, offer help. Jane Taber. The Globe and Mail. September 19, 2007.

- ↑ Canadian Press (September 28, 2007). "Ignatieff urges Libs to come together, says 'united we win, divided we lose.'" maclean's.ca. Retrieved on: October 6, 2007.

- ↑ Whittington, Les (2008) Ignatieff vows a new course, Toronto Star, November 14, 2008

- ↑ Ivison, John (2008) Ignatieff touted to lead Liberal-NDP coalition National Post, December 1, 2008

- ↑ Gunter, Lorne (2008) Ignatieff is too smart to topple Harper The Edmonton Journal, December 18, 2008

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 "New Leader of Canada's Liberal Party says ready to form coalition". People's Daily. 2008-12-11. http://english.people.com.cn/90001/90777/90852/6551205.html. Retrieved 2008-12-25.

- ↑ "Rae dropping out of Liberal leadership race". CBC News. 2008-12-09. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2008/12/09/rae-liberals.html. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ↑ "Ignatieff slams Harper for 'failure to unite Canada'". CBC News. 2009-05-02. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2009/05/02/liberal-convention.html. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ "Canada's government survives non-confidence motion | Canada | Reuters". Ca.reuters.com. 2009-10-01. http://ca.reuters.com/article/domesticNews/idCATRE58T4BE20091001. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Ignatieff closing in on Dion territory National Post:November 14, 2009

- ↑ "Official Report * Table of Contents * Number 025 (Official Version)". .parl.gc.ca. http://www2.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?pub=Hansard&doc=25&Language=E&Mode=1&Parl=39&Ses=1#T1800. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Clark, Campbell (May 19, 2006). "Vote divides Liberal hawks from doves". The Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/LAC.20060519.AFGHANLIBS19/TPStory/National. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 CTV.ca News Staff (May 17, 2006). "MPs narrowly vote to extend Afghanistan mission". CTV.ca. http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20060517/nato_afghan_060517/20060517?hub=CTVNewsAt11. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ Rana, F. Abbas; Persichilli, Angelo, and Vongdouangchanh (May 22, 2006). "Afghanistan vote leaves federal Liberals flat-footed". The Hill Times. http://www.hilltimes.com/html/index.php?display=story&full_path=/2006/may/22/afghan/&c=1. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ Bryden, John (May 18, 2006). "Harper may have used Afghan vote to ensare Ignatieff". The National Post. http://www.canada.com/nationalpost/news/story.html?id=07a874aa-4e70-488e-b622-ab611d640a09&k=26718. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ Dubinski, Kate (May 20, 2006). "Challenges to unity many, Ignatieff says". The London Free Press. http://lfpress.ca/newsstand/News/National/2006/05/20/1589327-sun.html. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ↑ "Priority Policy Resolutions" (PDF). Liberal Party of Canada (Quebec). October 21, 2006. http://qc.liberal.ca/images/dir/RÉSOLUTIONS%20PRIORITAIRES%20(en).pdf. Retrieved 2006-11-11.

- ↑ "Rivals cool to Quebec 'nation' debate". The Toronto Star. October 30, 2006. http://www.thestar.com/NASApp/cs/ContentServer?pagename=thestar/Layout/Article_PrintFriendly&c=Article&cid=1162162210312&call_pageid=1022181444328. Retrieved 2006-11-11.

- ↑ O'Neil, P. (August 21, 2006). "Ignatieff calls for 'carbon tax' to aid climate". Vancouver Sun. http://www2.canada.com/vancouversun/news/story.html?id=ed009175-7814-44f0-aa99-327a4209a259.

- ↑ Whittington, L. (Feb 28, 2009). Dion's carbon tax plan was a vote loser, Ignatieff says. The Toronto Star.

- ↑ "Honorary Graduates of The University of Stirling – 1988 to 1997". Externalrelations.stir.ac.uk. http://www.externalrelations.stir.ac.uk/events/honorary-graduates/1988-1997.php. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "University Senate". Queensu.ca. http://www.queensu.ca/secretariat/senate/HDfall01.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Report Of The Honorary Degrees Committee". Uwo.ca. 2001-09-21. http://www.uwo.ca/univsec/senate/minutes/2001/r0109hdg.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "UNB Honorary Degrees Database". Lib.unb.ca. http://www.lib.unb.ca/archives/HonoraryDegrees/results.php?action=browse&name=I&startswith=1. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ http://www.mcgill.ca/newsroom/news/item/?item_id=9790] [http://www.mcgill.ca/reporter/34/17/honorary/

- ↑ "University of Regina – External Relations". Uregina.ca. 2003-05-22. http://www.uregina.ca/news/newsreleases.php?release=323. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Honorary Degree Recipients (from present to 1890)". Whitman.edu. http://www.whitman.edu/content/commencement/history/honorary. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ [1]

External links

- Michael Ignatieff

- Michael Ignatieff - Parliament of Canada biography

- Michael Ignatieff Biography

- Michael Ignatieff at the Internet Movie Database

- "Michael Grant Ignatieff," from the Canadian Encyclopedia

Articles by Ignatieff

- The Meaning of Diana, Prospect Magazine, October 23, 1997. A review of Diana Spencer.

- Why Bush must send in his troops, The Guardian, April 19, 2002. On why Ignatieff believes a two-state solution is the last chance for Middle East peace.

- The Burden, The New York Times Magazine, January 5, 2003. Written just prior to the Iraq war, this article explains his support for the invasion.

- The Year of Living Dangerously, The New York Times Magazine, March 14, 2004. A follow-up to The Burden, discussing the war.

- Lesser Evils, The New York Times Magazine, May 2, 2004, An article on finding the balance between civil liberties and security.

- A Generous Helping of Liberal Brains, The Globe and Mail, March 4, 2005 (subscription). An excerpt from his address to the biennial policy conference of the Liberal Party.

- Who Are Americans to Think That Freedom Is Theirs to Spread? , The New York Times Magazine, June 26, 2005. Ignatieff On Spreading Democracy

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||